Google puts charging in employee parking lots — a great place to have it

The story of EV charging in 2022 revolved around fast DC charging and how to get more stations so people can fill up their EV in 30-40 minutes, and perhaps in just 10 minutes in the future. The Inflation Reduction Act and other laws have allocated huge subsidies to encourage the installation of such charging in cities and along rural highways. This is because to transition the world from gasoline to Electric Vehicles, it needs to be easy to charge those vehicles. For people still mired in “gasoline thinking” they think in terms of the “fill up,” where a driver drives around until their “tank” gets low, and then they look for a place to fill up, do so, and get on their way. Car Charging Points

Gasoline thinking is the wrong way to think about EVs, but we’ve thought that way for a century which makes it hard to change. To stop this thinking, we might consider a thought experiment of forbidding, rather than encouraging fast charging in the cities. Since fast charging does have its uses, we’re not actually going to ban it — particularly on the highways between cities — but if we don’t stamp out gasoline thinking, we’ll switch to EVs in the wrong way; a way that is less convenient and takes more time, and costs more money to boot. If we put our government funds and policy into fast charging, we’ll be putting them in the wrong place, and sacrificing better plans.

Fast charging still makes sense on road trips of course, and for high-utilization fleet vehicles. It also has become the inconvenient fallback for people who can’t access the superior slow-charging approach. So it would not actually be banned — don’t fret too much.

“EV thinking” is different. It’s based on the reality that almost all cars are parked for 90% or more of the day. If the cars can slow charge during even a small portion of that, they can get all the charge they need almost all the time. Charge where you park for long periods. The charging takes zero time out of the driver’s day, because it happens while the car was going to sit there parked anyway. It is also kinder to the battery. Slow charging equipment is also much cheaper than fast-charging gear, and as a result, the total charging costs are much lower. (Many fast charging stations charge a price that is more than the cost of gasoline in an efficient hybrid car, defeating the cost savings that are one of the big advantages of EVs.)

In the EV thinking world, you seek to have charging in a decent fraction of the city’s parking spaces. You want to make it so that most cars spend a few hours each day parked in one of those spaces. (Today, it’s the spaces used from midnight to 3pm. In the future it will be the spaces used from 9am to 3pm.) Cars drive an average of about 35 miles/day, and thus only need about 90 minutes per day — on average — in such a space. Most cars spend a lot of their time at the driver’s home, and 8-9 hours/day at their workplace or commuter parking lot.

For most people who own a home, this is already solved. There is electricity everywhere and those people pay anywhere from $200 to $1,000, once per home, to install charging. (Some face a much higher cost, discussed below.)

Of course, many people don’t own their parking space, and while they may also park at work, they don’t control their employer. This includes renters and even many condo owners. It also includes people who don’t have a space and park on the street. Today, the up-front cost of EVs keeps their adoption low, and as such the buyers often are people wealthy enough to be homeowners, but even so, there are already enough buyers who don’t own a space that DC Fast charging is growing in cities.

Don't put charging where nobody is parking

If public policy and money are to work to make EV charging infrastructure plentiful, the right place to do that is in the parking spaces used by people who don’t own their own space. One reason we have not gone for that solution is that these spaces are often private property, meant for one person. When it comes to policy and subsidies, it is much more natural to imagine applying them to publicly accessible chargers used by many people. We are wary of government money just going to subsidize owners of apartment buildings and office blocks.

In addition, the cost of putting in the EVSEs (which is the technical name for an AC charging interface, as there is no “charger” in it) can often be surprisingly high. An EVSE is a dead-simple device that does almost nothing. It’s just really a plug, wires, a high-current relay, and a small microcontroller. Tesla sells their quite nice mobile EVSE for $200, and others from Asia in that price range are becoming plentiful. Many people are pushed to much more expensive units costing $500-$700 even in homes, and the units sold for commercial installation in parking lots can easily be in the thousands. They justify that cost by being a bit more robust for public use, and having unnecessary things like credit card terminals and displays like the gas pumps of gasoline thinking. (Newer cars will soon all handle authentication and billing by computer through the charging cable, as Teslas have always done.)

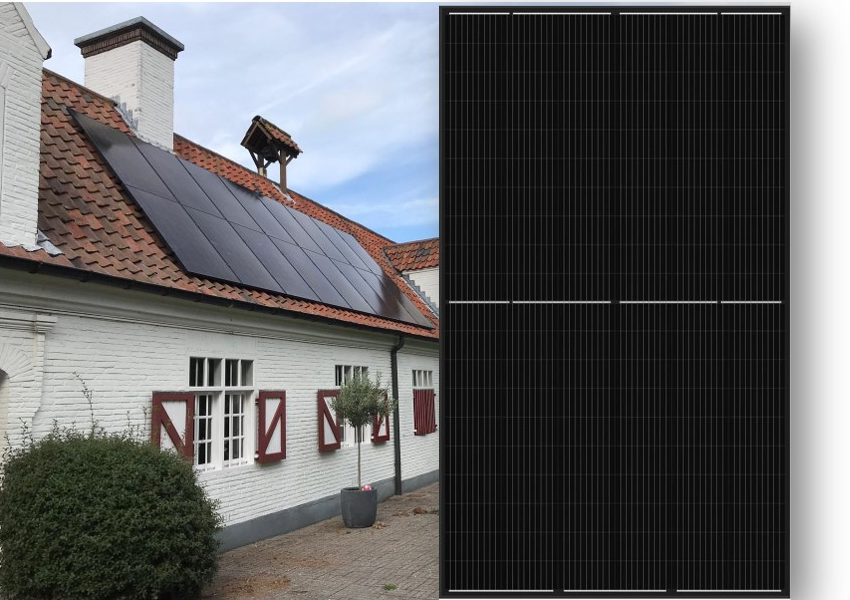

These solar chargers aren't connected to the grid, which is a waste, but sometimes construction and ... [+] permits and wiring can cost so much that this makes sense

Unfortunately, those multi-thousand dollar units don’t seem so pricey because of the cost of two other things — outdoor high-current wiring, with trenching and concrete pouring, and worst of all permits and high-end contractors, and the false belief that installing lots of charging requires upgrading the electrical service of a building and the ability to deliver full power to every stall at the same time. The costs can be so much that one company sells a standalone solar powered unit that can be dropped in a parking space by a flatbed with no permits and construction, and in spite of all the losses of off-grid solar, still beat the price of construction.

Several steps can be taken to lower the cost of installing charging where people park. These include lower-cost EVSEs, and safe but suitable modifications to electrical codes to lower the cost while maintaining proper safety. EVSEs are unlike old-world electrical devices, and have smart computer control to manage currents and monitor temperatures.

Smart multi-unit charging stations arrange to share the available current among the charging cars. Since most cars only need an average of 90 minutes at 7kW, but they are typically parked for 10 hours at night locations and 8 hours at work/commute locations, you don’t need 7kW per station. Even so, many electricians will calculate that because the charging stalls might deliver a large amount, like 40kW, it is necessary to increase the service to the building by at least 40kW to deal with the building being at maximum power and the cars all charging at the same time. In reality, most homes and buildings are not anywhere near their rated maximum power use most of the time, and never at night. New smarter charging technologies can measure the power use of the other loads at their site, and assure the cars never draw enough to bring the total load over its rated limit. As such, buildings can almost always install a charging stall for every EV owner without increasing the building’s electrical service, saving a lot of money. (Disclosure: While I have advocated for such approaches for many years, I recently invested in a company which makes such technology.)

It’s much easier to push for the installation of EV charging wiring in all new buildings and suitable parking lots. It’s much easier and cheaper to do this when building and doesn’t even need extra permits.

If the idea of not having fast charging in the cities sounds odd, you may not know that this was the original design of Tesla’s charging network, which was and still is by far the best fast-charging network. The original network didn’t have chargers in the cities, and when they first added them, they were half the power of the rural chargers. That’s changed but Tesla’s plan was to use the chargers only on road trips, where you do indeed need them.

Plug NYC electric vehicle charging station with two cars plugged in, Upper East Side, Manhattan. ... [+] (Photo by: Lindsey Nicholson/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Some people park on the street. There actually are solutions for the street, in particular when there are already power poles and overhead power lines to tap. Companies now design EVSEs that mount on power and light poles, with a charging cord that hangs down. These are easy because no construction is needed in many cases, and power may be in good supply. This is not always the case, and retrofitting some old streets is challenging. If these drivers can’t find a commute parking spot with charging, they may be left with fast charging, or waiting to get an electric car.

Well before the planned ending of gasoline car sales in 2035 in some states, cars will get basic self-driving abilities. Even those who don’t think we’ll see cars driving people around by then, it’s a much easier problem to have a car drive itself on quiet streets at lower speeds, particularly at night. In many locations, that’s all that’s needed for a car to drive itself to charging when it’s not in use — and again most cars are parked more than 90% of the time. It’s particularly easy at night — one reason that Cruise’s first step was to deploy robotaxi service in San Jose only at night.

The ideal car, from a charging standpoint, is one that is always magically full, and you’re not even aware of how it does it. Your car and phone will learn your habits and be able to guess times that make sense to wander off for charging. Some drivers that want to take advantage of this may explicitly communicate that it will be a few hours before they need the car again — a small burden compared to having to charge or even fill up a gasoline car. If those drivers want the car early they may need to signal that 5-10 minutes in advance. To serve such cars, charging need only be put in places it is cheap to put it, or cars may make use of spare capacity at office lots that sit unused at night. The big question is how they plug in. At first, charging lots for robocars might have a human attendant, like a full service gas station. Later, simple robotic plugs can do the job when the car does the work of positioning itself in the exact right position. In the long term, a new charging plug could be designed that goes on the front, back or bottom of a car — most today are on the side — allowing the car to do all the movement necessary to plug in.

While it’s better to make one slow charging stall per car, if you have auto plug-in you can make far fewer stalls and have the cars move in and out within the parking lot — that sort of self-driving is possible today, even with just cameras.

As noted, fast charging is important for road trips out of the city, and for fleets whose cars drive all day. While we won’t ban fast charging, what is the best way to change the thinking?

But also consider what not to do:

Recharging Station Of course, none of these subsidies or rules would be needed if burners of gasoline had to pay for the harm caused by the pollution (especially particulate matter) from these fuels. Instead, we currently subsidize oil and gas. In that situation, the cost of burning gasoline or diesel would make such cars only with those with money, as well as fuel to burn and most buyers would go electric without being asked — at least in places without coal-based grids. They would then demand their rental homes and condos have charging.